The Battle For Pakistan - Aug 1

From stratfor comes a video about the troubled state of Pakistan. Marla Dial and Kamran Bokhari give us the gritty details. Enjoy!

Johnny Cash

Sticking it to 'The Man' and Satan's minions for the glory of God.

From stratfor comes a video about the troubled state of Pakistan. Marla Dial and Kamran Bokhari give us the gritty details. Enjoy!

Johnny Cash

Posted by

Richard Bowers

on

Saturday, August 01, 2009

0

Salutations and Rants

![]()

Labels: Jihad, Kings of the East, Other Military, Stratfor, YouTube

'This is what the Sovereign LORD says: I am against you, O Gog, chief prince of Meshech and Tubal. I will turn you around, put hooks in your jaws and bring you out with your whole army—your horses, your horsemen fully armed, and a great horde with large and small shields, all of them brandishing their swords. Persia (Modern Iran - JC), Cush and Put will be with them, all with shields and helmets, also Gomer with all its troops, and Beth Togarmah from the far north with all its troops—the many nations with you.

(Ezekiel 38:3-6)

Something interesting has just happened in Iran. A massive presidential election has taken place with the incumbent Mahmoud Ahmadinejad being returned to office. Best to wait for the dust to settle before we can properly gauge what's really going on. Here's an interview with Dr. George Friedman (CEO of Stratfor) giving his assessment of the situation.

Johnny Cash

Posted by

Richard Bowers

on

Tuesday, June 16, 2009

2

Salutations and Rants

![]()

Labels: Bible Prophecy, Holy Land, Iran, Stratfor, U.S. and A, YouTube

Hope you're paying attention to what's happening in Mexico. It's certainly not 'The End', but it does represent one of many birth pangs we read about in scripture (see Matthew 24).

Johnny Cash

The world is suddenly facing the possibility of an influenza pandemic following outbreaks of swine flu. Indeed, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has declared a public health emergency — though largely for administrative and management purposes — to facilitate efforts to deal with the flu outbreak. We say “possibility of a pandemic” because, at this moment, it does not seem to us that anyone has a clear handle on either the likelihood of the virus’s dispersion, nor of its virulence. As of this writing, Mexican authorities suspect that as many as 86 people have died from the disease, although only 22 swine flu deaths have been officially confirmed. Sunday was rife with reports of cases emerging in states from California to New York (as well as in Canada, New Zealand, Spain, Brazil and Colombia), though there have been no reports of deaths or indications that deaths are imminent in these countries.

It might be the case that the virus is so widespread in Mexico that those who died from the disease represent a small percentage of the infected, whereas in the United States the virus has not finished incubating and thus has not yet begun to show its effects. At this point, virulence as a percentage of infection is not clear to us. Nevertheless, U.S. authorities have called a public health emergency, and the international disease control community is struggling to come up with a predictive model.

This situation is outside our area of expertise, though we are able to say that the traditional authorities on such matters appear to be quite unclear on what we are facing. What we can discuss are the potential implications of an influenza pandemic, even one substantially milder than what struck in 1918-1919, 1957-1958 or 1968-1969. In the first case, more than 500,000 people died in the United States alone; tens of thousands died in the United States in the latter two cases. (Flu season runs through the winter, traditionally peaking around February-March, with effects felt into the early summer.) Given the current time frame and the economic crisis, the implication of a new pandemic could be significant, even if it resulted in a much smaller death toll.

The world is currently struggling to emerge from an economic crisis, and at this point some minor headway appears to have been made. The most important impact of this virus would be economic. Apart from absences from work –- or even the potential loss of a portion of the work force — a pandemic could be utterly disruptive.

It is difficult to avoid catching the flu, but one way to decrease the odds is to avoid exposure to others, particularly in crowds, and to stay out of the office if they begin to experience symptoms — and for several days after symptoms cease. In the case of a pandemic, that advice would almost certainly be given.

That in turn could drive a stake into the heart of consumer spending, which is already more than a little weak. If the disease — or popular perception of the disease — were to reach pandemic proportions, consumers could begin to view an impulse trip to the mall as potentially a life-or-death choice. Discretionary spending would collide with discretion, as individuals started to forgo trips that would bring them into contact with large numbers of people –- not just at major sporting events and public rallies, but also movies and restaurants.

Depending on the extent of the virus’s spread, it could directly affect production: Offices and factories would shut down in areas where the flu was particularly rampant, amid efforts to control it. International travel and trade might well be affected, both voluntarily (as people avoided travel and refused to buy goods from countries heavily infected) and involuntarily (as states acted to protect their populations).

The greatest effect would be psychological. In a world where consumer confidence has already been deeply affected by the economic downturn, a pandemic would dramatically darken the mood of the international system, with potential impact on governments.

We are not trying to be alarmist. As stated, we do not really know what these swine flu infections and deaths mean, and as with many other scares, this situation might dissipate in a matter of days. There have been plenty of scares about avian strains of the flu virus breaking through the human-to-human transmission barrier, and so far they have been unfounded. Even the widely hyped outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), which spread rapidly from China to a number of other countries in 2002 and 2003, ultimately was contained. Fewer than 800 fatalities from SARS occurred worldwide, with only eight confirmed cases (and zero deaths) in the United States, despite widespread concern that the disease could severely impact the American populace.

But timing can be everything. We are acutely aware that if a deadly flu pandemic were to strike right now — whether actually proving to be, or just creating the perception of, a rapidly spreading and lethal disease — the effect on economic recovery could quickly become dramatic, and therefore the nature of politics in many countries would shift. This is not a geopolitical event in itself, but given the worst-case scenarios, it well might have a geopolitical effect.

Posted by

Richard Bowers

on

Tuesday, April 28, 2009

1 Salutations and Rants

![]()

Labels: Stratfor

President Barack Obama was in Arizona recently selling his mortgage relief plan. As stratfor notes, this 'concentrates an unprecedented amount of financial power in government hands'. It also dovetails perfectly with Bible prophecy. If more and more money can be funneled into fewer and fewer hands, then all the money (and all the power) can be bestowed to one man. Lenin (and Jesus) was right! Imperialism is the highest form of capitalism.

Johnny Cash

Posted by

Richard Bowers

on

Thursday, February 19, 2009

0

Salutations and Rants

![]()

Labels: Money, One World Gov't, Stratfor, U.S. and A

Got another good here from stratfor on Obama's decision to surge into Afghanistan. Stratfor argues for a reduced role in conventional forces while maintaining a robust intelligence role. As in any war the locals will support the side that's winning. Unfortunately that side doesn't appear to be us.

Johnny Cash

Strategic Divergence: The War Against the Taliban and the War Against Al Qaeda

January 26, 2009

By George Friedman

Washington’s attention is now zeroing in on Afghanistan. There is talk of doubling U.S. forces there, and preparations are being made for another supply line into Afghanistan — this one running through the former Soviet Union — as an alternative or a supplement to the current Pakistani route. To free up more resources for Afghanistan, the U.S. withdrawal from Iraq probably will be accelerated. And there is discussion about whether the Karzai government serves the purposes of the war in Afghanistan. In short, U.S. President Barack Obama’s campaign promise to focus on Afghanistan seems to be taking shape.

We have discussed many aspects of the Afghan war in the past; it is now time to focus on the central issue. What are the strategic goals of the United States in Afghanistan? What resources will be devoted to this mission? What are the intentions and capabilities of the Taliban and others fighting the United States and its NATO allies? Most important, what is the relationship between the war against the Taliban and the war against al Qaeda? If the United States encounters difficulties in the war against the Taliban, will it still be able to contain not only al Qaeda but other terrorist groups? Does the United States need to succeed against the Taliban to be successful against transnational Islamist terrorists? And assuming that U.S. forces are built up in Afghanistan and that the supply problem through Pakistan is solved, are the defeat of Taliban and the disruption of al Qaeda likely?

Al Qaeda and U.S. Goals Post-9/11

The overarching goal of the United States since Sept. 11, 2001, has been to prevent further attacks by al Qaeda in the United States. Washington has used two means toward this end. One was defensive, aimed at increasing the difficulty of al Qaeda operatives to penetrate and operate within the United States. The second was to attack and destroy al Qaeda prime, the group around Osama bin Laden that organized and executed 9/11 and other attacks in Europe. It is this group — not other groups that call themselves al Qaeda but only are able to operate in the countries where they were formed — that was the target of the United States, because this was the group that had demonstrated the ability to launch intercontinental strikes.

Al Qaeda prime had its main headquarters in Afghanistan. It was not an Afghan group, but one drawn from multiple Islamic countries. It was in alliance with an Afghan group, the Taliban. The Taliban had won a civil war in Afghanistan, creating a coalition of support among tribes that had given the group control, direct or indirect, over most of the country. It is important to remember that al Qaeda was separate from the Taliban; the former was a multinational force, while the Taliban were an internal Afghan political power.

The United States has two strategic goals in Afghanistan. The first is to destroy the remnants of al Qaeda prime — the central command of al Qaeda — in Afghanistan. The second is to use Afghanistan as a base for destroying al Qaeda in Pakistan and to prevent the return of al Qaeda to Afghanistan.

To achieve these goals, Washington has sought to make Afghanistan inhospitable to al Qaeda. The United States forced the Taliban from Afghanistan’s main cities and into the countryside, and established a new, anti-Taliban government in Kabul under President Hamid Karzai. Washington intended to deny al Qaeda bases in Afghanistan by unseating the Taliban government, creating a new pro-American government and then using Afghanistan as a base against al Qaeda in Pakistan.

The United States succeeded in forcing the Taliban from power in the sense that in giving up the cities, the Taliban lost formal control of the country. To be more precise, early in the U.S. attack in 2001, the Taliban realized that the massed defense of Afghan cities was impossible in the face of American air power. The ability of U.S. B-52s to devastate any concentration of forces meant that the Taliban could not defend the cities, but had to withdraw, disperse and reform its units for combat on more favorable terms.

At this point, we must separate the fates of al Qaeda and the Taliban. During the Taliban retreat, al Qaeda had to retreat as well. Since the United States lacked sufficient force to destroy al Qaeda at Tora Bora, al Qaeda was able to retreat into northwestern Pakistan. There, it enjoys the advantages of terrain, superior tactical intelligence and support networks.

Even so, in nearly eight years of war, U.S. intelligence and special operations forces have maintained pressure on al Qaeda in Pakistan. The United States has imposed attrition on al Qaeda, disrupting its command, control and communications and isolating it. In the process, the United States used one of al Qaeda’s operational principles against it. To avoid penetration by hostile intelligence services, al Qaeda has not recruited new cadres for its primary unit. This makes it very difficult to develop intelligence on al Qaeda, but it also makes it impossible for al Qaeda to replace its losses. Thus, in a long war of attrition, every loss imposed on al Qaeda has been irreplaceable, and over time, al Qaeda prime declined dramatically in effectiveness — meaning it has been years since it has carried out an effective operation.

The situation was very different with the Taliban. The Taliban, it is essential to recall, won the Afghan civil war that followed the Soviet withdrawal despite Russian and Iranian support for its opponents. That means the Taliban have a great deal of support and a strong infrastructure, and, above all, they are resilient. After the group withdrew from Afghanistan’s cities and lost formal power post-9/11, it still retained a great deal of informal influence — if not control — over large regions of Afghanistan and in areas across the border in Pakistan. Over the years since the U.S. invasion, the Taliban have regrouped, rearmed and increased their operations in Afghanistan. And the conflict with the Taliban has now become a conventional guerrilla war.

The Taliban and the Guerrilla Warfare Challenge

The Taliban have forged relationships among many Afghan (and Pakistani) tribes. These tribes have been alienated by Karzai and the Americans, and far more important, they do not perceive the Americans and Karzai as potential winners in the Afghan conflict. They recall the Russian and British defeats. The tribes have long memories, and they know that foreigners don’t stay very long. Betting on the United States and Karzai — when the United States has sent only 30,000 troops to Afghanistan, and is struggling with the idea of sending another 30,000 troops — does not strike them as prudent. The United States is behaving like a power not planning to win; and, in any event, they would not be much impressed if the Americans were planning to win.

The tribes therefore do not want to get on the wrong side of the Taliban. That means they aid and shelter Taliban forces, and provide them intelligence on enemy movement and intentions. With its base camps and supply lines running from Pakistan, the Taliban are thus in a position to recruit, train and arm an increasingly large force.

The Taliban have the classic advantage of guerrillas operating in known terrain with a network of supporters: superior intelligence. They know where the Americans are, what the Americans are doing and when the Americans are going to strike. The Taliban declines combat on unfavorable terms and strikes when the Americans are weakest. The Americans, on the other hand, have the classic problem of counterinsurgency: They enjoy superior force and firepower, and can defeat anyone they can locate and pin down, but they lack intelligence. As much as technical intelligence from unmanned aerial vehicles and satellites is useful, human intelligence is the only effective long-term solution to defeating an insurgency. In this, the Taliban have the advantage: They have been there longer, they are in more places and they are not going anywhere.

There is no conceivable force the United States can deploy to pacify Afghanistan. A possible alternative is moving into Pakistan to cut the supply lines and destroy the Taliban’s base camps. The problem is that if the Americans lack the troops to successfully operate in Afghanistan, it is even less likely they have the troops to operate in both Afghanistan and Pakistan. The United States could use the Korean War example, taking responsibility for cutting the Taliban off from supplies and reinforcements from Pakistan, but that assumes that the Afghan government has an effective force motivated to engage and defeat the Taliban. The Afghan government doesn’t.

The obvious American solution — or at least the best available solution — is to retreat to strategic Afghan points and cities and protect the Karzai regime. The problem here is that in Afghanistan, holding the cities doesn’t give the key to the country; rather, holding the countryside gives the key to the cities. Moreover, a purely defensive posture opens the United States up to the Dien Bien Phu/Khe Sanh counterstrategy, in which guerrillas shift to positional warfare, isolate a base and try to overrun in it.

A purely defensive posture could create a stalemate, but nothing more. That stalemate could create the foundations for political negotiations, but if there is no threat to the enemy, the enemy has little reason to negotiate. Therefore, there must be strikes against Taliban concentrations. The problem is that the Taliban know that concentration is suicide, and so they work to deny the Americans valuable targets. The United States can exhaust itself attacking minor targets based on poor intelligence. It won’t get anywhere.

U.S. Strategy in Light of al Qaeda’s Diminution

From the beginning, the Karzai government has failed to take control of the countryside. Therefore, al Qaeda has had the option to redeploy into Afghanistan if it chose. It didn’t because it is risk-averse. That may seem like a strange thing to say about a group that flies planes into buildings, but what it means is that the group’s members are relatively few, so al Qaeda cannot risk operational failures. It thus keeps its powder dry and stays in hiding.

This then frames the U.S. strategic question. The United States has no intrinsic interest in the nature of the Afghan government. The United States is interested in making certain the Taliban do not provide sanctuary to al Qaeda prime. But it is not clear that al Qaeda prime is operational anymore. Some members remain, putting out videos now and then and trying to appear fearsome, but it would seem that U.S. operations have crippled al Qaeda.

So if the primary reason for fighting the Taliban is to keep al Qaeda prime from having a base of operations in Afghanistan, that reason might be moot now as al Qaeda appears to be wrecked. This is not to say that another Islamist terrorist group could not arise and develop the sophisticated methods and training of al Qaeda prime. But such a group could deploy many places, and in any case, obtaining the needed skills in moving money, holding covert meetings and the like is much harder than it looks — and with many intelligence services, including those in the Islamic world, on the lookout for this, recruitment would be hard.

It is therefore no longer clear that resisting the Taliban is essential for blocking al Qaeda: al Qaeda may simply no longer be there. (At this point, the burden of proof is on those who think al Qaeda remains operational.)

Two things emerge from this. First, the search for al Qaeda and other Islamist groups is an intelligence matter best left to the covert capabilities of U.S. intelligence and Special Operations Command. Defeating al Qaeda does not require tens of thousands of troops — it requires excellent intelligence and a special operations capability. That is true whether al Qaeda is in Pakistan or Afghanistan. Intelligence, covert forces and airstrikes are what is needed in this fight, and of the three, intelligence is the key.

Second, the current strategy in Afghanistan cannot secure Afghanistan, nor does it materially contribute to shutting down al Qaeda. Trying to hold some cities and strategic points with the number of troops currently under consideration is not an effective strategy to this end; the United States is already ceding large areas of Afghanistan to the Taliban that could serve as sanctuary for al Qaeda. Protecting the Karzai government and key cities is therefore not significantly contributing to the al Qaeda-suppression strategy.

In sum, the United States does not control enough of Afghanistan to deny al Qaeda sanctuary, can’t control the border with Pakistan and lacks effective intelligence and troops for defeating the Taliban.

Logic argues, therefore, for the creation of a political process for the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan coupled with a recommitment to intelligence operations against al Qaeda. Ultimately, the United States must protect itself from radical Islamists, but cannot create a united, pro-American Afghanistan. That would not happen even if the United States sent 500,000 troops there, which it doesn’t have anyway.

A Tale of Two Surges

The U.S. strategy now appears to involve trying a surge, or sending in more troops and negotiating with the Taliban, mirroring the strategy used in Iraq. But the problem with that strategy is that the Taliban don’t seem inclined to make concessions to the United States. The Taliban don’t think the United States can win, and they know the United States won’t stay. The Petraeus strategy is to inflict enough pain on the Taliban to cause them to rethink their position, which worked in Iraq. But it did not work in Vietnam. So long as the Taliban have resources flowing and can survive American attacks, they will calculate that they can outlast the Americans. This has been Afghan strategy for centuries, and it worked against the British and Russians.

If it works against the Americans, too, splitting the al Qaeda strategy from the Taliban strategy will be the inevitable outcome for the United States. In that case, the CIA will become the critical war fighter in the theater, while conventional forces will be withdrawn. It follows that Obama will need to think carefully about his approach to intelligence.

This is not an argument that al Qaeda is no longer a threat, although the threat appears diminished. Nor is it an argument that dealing with terrorism in Afghanistan and Pakistan is not a priority. Instead, it is an argument that the defeat of the Taliban under rationally anticipated circumstances is unlikely and that a negotiated settlement in Afghanistan will be much more difficult and unlikely than the settlement was in Iraq — but that even so, a robust effort against Islamist terror groups must continue regardless of the outcome of the war with the Taliban.

Therefore, we expect that the United States will separate the two conflicts in response to these realities. This will mean that containing terrorists will not be dependent on defeating or holding out against the Taliban, holding Afghanistan’s cities, or preserving the Karzai regime. We expect the United States to surge troops into Afghanistan, but in due course, the counterterrorist portion will diverge from the counter-Taliban portion. The counterterrorist portion will be maintained as an intense covert operation, while the overt operation will wind down over time. The Taliban ruling Afghanistan is not a threat to the United States, so long as intense counterterrorist operations continue there.

The cost of failure in Afghanistan is simply too high and the connection to counterterrorist activities too tenuous for the two strategies to be linked. And since the counterterror war is already distinct from conventional operations in much of Afghanistan and Pakistan, our forecast is not really that radical.

Posted by

Richard Bowers

on

Tuesday, January 27, 2009

0

Salutations and Rants

![]()

Labels: Jihad, Kings of the East, Other Military, Stratfor

Here are four maps from stratfor on Operation Cast Lead. The maps are in chronological order from the earliest at the top to the most recent at the bottom. Click on each individual map for a full view. Cheers, JC

Posted by

Richard Bowers

on

Tuesday, January 06, 2009

0

Salutations and Rants

![]()

Labels: Anti-Semitism, Holy Land, Jihad, Other Military, Stratfor

No Christmas theme here. Very interesting stuff from stratfor's latest. As it turns out, neither the FBI nor the Washington Post were as altruistic as originally thought. Do we dare call it treason to conspire against a sitting president even if that president is a S.O.B.? Either way you slice it, Felt's betrayal of Nixon (with Woodward and Bernstein being the beneficiaries) had more to do with ego and ambition than patriotic duty. A must read!

Johnny Cash

The Death of Deep Throat and the Crisis of Journalism

December 22, 2008 | 1659 GMT

By George Friedman

Mark Felt died last week at the age of 95. For those who don’t recognize that name, Felt was the “Deep Throat” of Watergate fame. It was Felt who provided Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of The Washington Post with a flow of leaks about what had happened, how it happened and where to look for further corroboration on the break-in, the cover-up, and the financing of wrongdoing in the Nixon administration. Woodward and Bernstein’s exposé of Watergate has been seen as a high point of journalism, and their unwillingness to reveal Felt’s identity until he revealed it himself three years ago has been seen as symbolic of the moral rectitude demanded of journalists.

In reality, the revelation of who Felt was raised serious questions about the accomplishments of Woodward and Bernstein, the actual price we all pay for journalistic ethics, and how for many years we did not know a critical dimension of the Watergate crisis. At a time when newspapers are in financial crisis and journalism is facing serious existential issues, Watergate always has been held up as a symbol of what journalism means for a democracy, revealing truths that others were unwilling to uncover and grapple with. There is truth to this vision of journalism, but there is also a deep ambiguity, all built around Felt’s role. This is therefore not an excursion into ancient history, but a consideration of two things. The first is how journalists become tools of various factions in political disputes. The second is the relationship between security and intelligence organizations and governments in a Democratic society.

Watergate was about the break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington. The break-in was carried out by a group of former CIA operatives controlled by individuals leading back to the White House. It was never proven that then-U.S. President Richard Nixon knew of the break-in, but we find it difficult to imagine that he didn’t. In any case, the issue went beyond the break-in. It went to the cover-up of the break-in and, more importantly, to the uses of money that financed the break-in and other activities. Numerous aides, including the attorney general of the United States, went to prison. Woodward and Bernstein, and their newspaper, The Washington Post, aggressively pursued the story from the summer of 1972 until Nixon’s resignation. The episode has been seen as one of journalism’s finest moments. It may have been, but that cannot be concluded until we consider Deep Throat more carefully.

Deep Throat Reconsidered

Mark Felt was deputy associate director of the FBI (No. 3 in bureau hierarchy) in May 1972, when longtime FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover died. Upon Hoover’s death, Felt was second to Clyde Tolson, the longtime deputy and close friend to Hoover who by then was in failing health himself. Days after Hoover’s death, Tolson left the bureau.

Felt expected to be named Hoover’s successor, but Nixon passed him over, appointing L. Patrick Gray instead. In selecting Gray, Nixon was reaching outside the FBI for the first time in the 48 years since Hoover had taken over. But while Gray was formally acting director, the Senate never confirmed him, and as an outsider, he never really took effective control of the FBI. In a practical sense, Felt was in operational control of the FBI from the break-in at the Watergate in August 1972 until June 1973.

Nixon’s motives in appointing Gray certainly involved increasing his control of the FBI, but several presidents before him had wanted this, too, including John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. Both of these presidents wanted Hoover gone for the same reason they were afraid to remove him: He knew too much. In Washington, as in every capital, knowing the weaknesses of powerful people is itself power — and Hoover made it a point to know the weaknesses of everyone. He also made it a point to be useful to the powerful, increasing his overall value and his knowledge of the vulnerabilities of the powerful.

Hoover’s death achieved what Kennedy and Johnson couldn’t do. Nixon had no intention of allowing the FBI to continue as a self-enclosed organization outside the control of the presidency and everyone else. Thus, the idea that Mark Felt, a man completely loyal to Hoover and his legacy, would be selected to succeed Hoover is in retrospect the most unlikely outcome imaginable.

Felt saw Gray’s selection as an unwelcome politicization of the FBI (by placing it under direct presidential control), an assault on the traditions created by Hoover and an insult to his memory, and a massive personal disappointment. Felt was thus a disgruntled employee at the highest level. He was also a senior official in an organization that traditionally had protected its interests in predictable ways. (By then formally the No. 2 figure in FBI, Felt effectively controlled the agency given Gray’s inexperience and outsider status.) The FBI identified its enemies, then used its vast knowledge of its enemies’ wrongdoings in press leaks designed to be as devastating as possible. While carefully hiding the source of the information, it then watched the victim — who was usually guilty as sin — crumble. Felt, who himself was later convicted and pardoned for illegal wiretaps and break-ins, was not nearly as appalled by Nixon’s crimes as by Nixon’s decision to pass him over as head of the FBI. He merely set Hoover’s playbook in motion.

Woodward and Bernstein were on the city desk of The Washington Post at the time. They were young (29 and 28), inexperienced and hungry. We do not know why Felt decided to use them as his conduit for leaks, but we would guess he sought these three characteristics — as well as a newspaper with sufficient gravitas to gain notice. Felt obviously knew the two had been assigned to a local burglary, and he decided to leak what he knew to lead them where he wanted them to go. He used his knowledge to guide, and therefore control, their investigation.

Systematic Spying on the President

And now we come to the major point. For Felt to have been able to guide and control the young reporters’ investigation, he needed to know a great deal of what the White House had done, going back quite far. He could not possibly have known all this simply through his personal investigations. His knowledge covered too many people, too many operations, and too much money in too many places simply to have been the product of one of his side hobbies. The only way Felt could have the knowledge he did was if the FBI had been systematically spying on the White House, on the Committee to Re-elect the President and on all of the other elements involved in Watergate. Felt was not simply feeding information to Woodward and Bernstein; he was using the intelligence product emanating from a section of the FBI to shape The Washington Post’s coverage.

Instead of passing what he knew to professional prosecutors at the Justice Department — or if he did not trust them, to the House Judiciary Committee charged with investigating presidential wrongdoing — Felt chose to leak the information to The Washington Post. He bet, or knew, that Post editor Ben Bradlee would allow Woodward and Bernstein to play the role Felt had selected for them. Woodward, Bernstein and Bradlee all knew who Deep Throat was. They worked with the operational head of the FBI to destroy Nixon, and then protected Felt and the FBI until Felt came forward.

In our view, Nixon was as guilty as sin of more things than were ever proven. Nevertheless, there is another side to this story. The FBI was carrying out espionage against the president of the United States, not for any later prosecution of Nixon for a specific crime (the spying had to have been going on well before the break-in), but to increase the FBI’s control over Nixon. Woodward, Bernstein and above all, Bradlee, knew what was going on. Woodward and Bernstein might have been young and naive, but Bradlee was an old Washington hand who knew exactly who Felt was, knew the FBI playbook and understood that Felt could not have played the role he did without a focused FBI operation against the president. Bradlee knew perfectly well that Woodward and Bernstein were not breaking the story, but were having it spoon-fed to them by a master. He knew that the president of the United States, guilty or not, was being destroyed by Hoover’s jilted heir.

This was enormously important news. The Washington Post decided not to report it. The story of Deep Throat was well-known, but what lurked behind the identity of Deep Throat was not. This was not a lone whistle-blower being protected by a courageous news organization; rather, it was a news organization being used by the FBI against the president, and a news organization that knew perfectly well that it was being used against the president. Protecting Deep Throat concealed not only an individual, but also the story of the FBI’s role in destroying Nixon.

Again, Nixon’s guilt is not in question. And the argument can be made that given John Mitchell’s control of the Justice Department, Felt thought that going through channels was impossible (although the FBI was more intimidating to Mitchell than the other way around). But the fact remains that Deep Throat was the heir apparent to Hoover — a man not averse to breaking the law in covert operations — and Deep Throat clearly was drawing on broader resources in the FBI, resources that had to have been in place before Hoover’s death and continued operating afterward.

Burying a Story to Get a Story

Until Felt came forward in 2005, not only were these things unknown, but The Washington Post was protecting them. Admittedly, the Post was in a difficult position. Without Felt’s help, it would not have gotten the story. But the terms Felt set required that a huge piece of the story not be told. The Washington Post created a morality play about an out-of-control government brought to heel by two young, enterprising journalists and a courageous newspaper. That simply wasn’t what happened. Instead, it was about the FBI using The Washington Post to leak information to destroy the president, and The Washington Post willingly serving as the conduit for that information while withholding an essential dimension of the story by concealing Deep Throat’s identity.

Journalists have celebrated the Post’s role in bringing down the president for a generation. Even after the revelation of Deep Throat’s identity in 2005, there was no serious soul-searching on the omission from the historical record. Without understanding the role played by Felt and the FBI in bringing Nixon down, Watergate cannot be understood completely. Woodward, Bernstein and Bradlee were willingly used by Felt to destroy Nixon. The three acknowledged a secret source, but they did not reveal that the secret source was in operational control of the FBI. They did not reveal that the FBI was passing on the fruits of surveillance of the White House. They did not reveal the genesis of the fall of Nixon. They accepted the accolades while withholding an extraordinarily important fact, elevating their own role in the episode while distorting the actual dynamic of Nixon’s fall.

Absent any widespread reconsideration of the Post’s actions during Watergate in the three years since Felt’s identity became known, the press in Washington continues to serve as a conduit for leaks of secret information. They publish this information while protecting the leakers, and therefore the leakers’ motives. Rather than being a venue for the neutral reporting of events, journalism thus becomes the arena in which political power plays are executed. What appears to be enterprising journalism is in fact a symbiotic relationship between journalists and government factions. It may be the best path journalists have for acquiring secrets, but it creates a very partial record of events — especially since the origin of a leak frequently is much more important to the public than the leak itself.

The Felt experience is part of an ongoing story in which journalists’ guarantees of anonymity to sources allow leakers to control the news process. Protecting Deep Throat’s identity kept us from understanding the full dynamic of Watergate. We did not know that Deep Throat was running the FBI, we did not know the FBI was conducting surveillance on the White House, and we did not know that the Watergate scandal emerged not by dint of enterprising journalism, but because Felt had selected Woodward and Bernstein as his vehicle to bring Nixon down. And we did not know that the editor of The Washington Post allowed this to happen. We had a profoundly defective picture of the situation, as defective as the idea that Bob Woodward looks like Robert Redford.

Finding the truth of events containing secrets is always difficult, as we know all too well. There is no simple solution to this quandary. In intelligence, we dream of the well-placed source who will reveal important things to us. But we also are aware that the information provided is only the beginning of the story. The rest of the story involves the source’s motivation, and frequently that motivation is more important than the information provided. Understanding a source’s motivation is essential both to good intelligence and to journalism. In this case, keeping secret the source kept an entire — and critical — dimension of Watergate hidden for a generation. Whatever crimes Nixon committed, the FBI had spied on the president and leaked what it knew to The Washington Post in order to destroy him. The editor of The Washington Post knew that, as did Woodward and Bernstein. We do not begrudge them their prizes and accolades, but it would have been useful to know who handed them the story. In many ways, that story is as interesting as the one about all the president’s men.

Posted by

Richard Bowers

on

Tuesday, December 23, 2008

0

Salutations and Rants

![]()

Labels: Crime/Immorality, Obituaries, Stratfor, U.S. and A

I'm actually rather surprised Mr. Harper and the Conservatives did so well. In this article stratfor suggests this win will embolden the separatist movement in Quebec. Actually, that's nothing new. We've been dealing with that problem since confederation.

Johnny Cash

Canada: Risky Strategies and a Conservative Victory

October 15, 2008 | 1814 GMT

The Conservative Party of Canada has been returned to power, albeit with a much stronger minority, election results released Oct. 15 show. But in his electoral bid, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper might have reinvigorated the cause of Quebec separatism.

Analysis

The Conservative Party of Canada, led by Prime Minister Stephen Harper, has won Canada’s Oct. 14 election, results released Oct. 15 show. Though the Conservative Party fell short of winning a majority in parliament (which requires 155 seats), the 143 seats (up from 126) it did win give it almost 50 percent more seats than its main rival, the Liberal Party, which placed second with 76 seats. The Bloc Quebecois came in third place with 50 seats, while the New Democrat Party (NDP) placed fourth with 37 seats.

In winning the election, however, the Harper government pursued a strategy that might have far-reaching consequences in Quebec.

After the election, the Harper government has more seats than it had before, and it probably will be able to govern effectively — at least in the short term — as if it were a majority party. By contrast, the main opposition Liberal Party went from 103 to 76 seats and is facing calls for new party leadership. The NDP experienced a sizeable gain (up from 29), but its 37 seats still make it a small opposition party.

Harper’s win will allow him to carry on with existing policies. These include maintaining Canada’s military commitment to Afghanistan through 2011 (whether the Harper government will be able to extend the mission beyond that date remains in question), as well as managing Ottawa’s budget surplus to deal with fallout from the global economic crisis and a slowing economy.

But in the process of campaigning, the Harper government introduced a threat to Canada’s confederal system of government. In an effort to win a majority, Harper campaigned heavily in Quebec, a province whose internal politics are historically dominated by concerns for the survival of the province’s Francophone identity. Harper, an Anglophone Canadian who was born in Toronto and spent his adulthood in the western province of Alberta — a province as decentralist and anti-Francophone as one gets in Canada — aimed to gain the Quebecois vote by appealing to the province’s character as a “nation” (as he did in a speech in Quebec City on July 3).

Identifying Quebec as a nation distinct from Anglophone Canada is the strategy Quebec separatists have used to gain support for their goal of separating the province from the rest of Canada and becoming an independent state. Harper’s recent predecessors from both major Canadian political parties — including Paul Martin, Jean Chretien, Brian Mulroney and Pierre Trudeau — all hailed from Quebec. They took a strongly centralist approach to the province, facing significant resistance from the province’s Francophone separatists.

Harper’s reaching out to the Quebecois “nation” threatens to undermine his predecessor’s legacies of federalism. The separatist-seeking Bloc Quebecois can be expected to use the 50 seats it won as a platform to champion pro-Quebec causes. Should Quebecois politicians propose another referendum on independence (one held in 1995 fell just barely short of a majority), they will have Harper’s usage of the term “nation” — by an Anglophone prime minister no less — to support their campaign.

Harper is not about to govern over the end of Canadian unity. But regionalism in Canada is clearly strengthening. The conservatives themselves had to regroup in the 1990s, bringing together remnants of the former Progressive Conservative Party as well as what was then the Reform Party of Canada (a Western regional party that morphed into the Canadian Alliance) to become a force in Canadian politics after the Progessive Conservative Party’s disastrous loss in 1993 elections. The Liberal Party, which appeals to very few voters west of Ontario province, might have to similarly regroup and create a new coalition to make a credible run for power again. Getting all the factions within the Liberal Party to agree on a new leader will be a first order of business.

The Harper government will likely counter any separatist challenge the old-fashioned way — by throwing money into Quebec and keeping it a loose, first-among-equals province. But that strategy risks having other provinces demand their share of federal monies, or, in the case of energy-rich Alberta, demand greater autonomy and a reduction in the share of its taxes that goes to Ottawa.

The net result of the Oct. 14 election might enshrine Ottawa as the arbiter of Canadian foreign and defense policy, while leaving economic and social policies to be determined at provincial government levels. This means coordination and cooperation among Canadian provinces could begin to unravel.

Posted by

Richard Bowers

on

Wednesday, October 15, 2008

0

Salutations and Rants

![]()

Labels: Canadian Politics, Stratfor

Without doubt the most dangerous place on earth right now is the Afgan-Pakistani border. So long as Canadian troops are there, the security and stability of Pakistan is paramount. Iran, Iraq, and North Korea seem tame by way of comparison. Below is a picture of a UH-60 Blackhawk helicopter in the area of operations.

Johnny Cash

Pakistan, U.S.: Dangerous Tensions Thursday, September 25, 2008 4:12PM

Pakistani forces fired at U.S. military helicopters along the Afghan-Pakistani border, the Pentagon said Sept. 25. The border dispute highlights the dangers of the high tensions between Islamabad and Washington — tensions that are likely to get worse before there is any hope that they will get better.

Analysis

Pakistani forces fired upon U.S. military helicopters along the Afghan-Pakistani border, the Pentagon confirmed Sept. 25. However, a Pentagon spokesman denied Pakistani claims that the helicopters had entered Pakistani airspace. Islamabad later claimed that only “warning shots” were fired and later insisted that only signal flares were fired to warn the helicopters off.

This incident — almost a textbook border dispute, complete with each side claiming it was in the right place in an area where the precise border often is not clear, and subsequent revisions of statements — highlights the dangers of tensions as high as they are between Pakistan and the United States. For Washington, Islamabad’s lack of control over the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) is providing a safe haven for Taliban and foreign jihadist fighters as well as a vector for arms feeding the Afghan insurgency. For Pakistan, the United States’ increasingly overt and unilateral raids and strikes on Pakistani territory are challenging Islamabad’s sovereignty, and with it the support of its people.

Thus, Pakistan has increasingly threatened to forcefully oppose any further U.S. intrusion, though the only casualty so far has been an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) that crashed in the region Sept. 23 — possibly for unrelated technical reasons. Indeed, though often flying well above the range of “trash fire” — small arms and anti-aircraft artillery — UAVs make a good intermediate step for Islamabad to demonstrate its resolve on the issue without firing upon U.S. servicemen. Islamabad cannot hope to garner public support for the fight against its own jihadist insurgency while U.S. forces continue to engage in unilateral strikes in the country.

Meanwhile, unless a Pakistani patrol catches helicopters flying low, the danger from small arms fire is not particularly extreme. Nevertheless, should Islamabad begin to employ more capable air defense weapons, the situation could quickly escalate — though Pakistan’s most capable air defense systems will remain committed to the Indian border. Both sides compound the potential for escalation.

On the Pakistani side, the paramilitary Frontier Corps patrols much of the border. The corps harbors more intense local tribal loyalties — likely making any given patrol more inclined to shoot and more likely to be aggressive in trying to bring down whatever U.S. target they might stumble upon, even if it is only approaching the border. The Frontier Corps is also likely to have individuals with conflicting loyalties — a situation that militants can exploit to deliberately trigger a U.S.-Pakistani clash, which would work to their advantage. The Frontier Corps or other forces in the area also have broad direction from Islamabad — compounded by high profile public statements by senior officials that Pakistan will defend its own territory — that they can interpret as they see fit and act on their own at the tactical level. Moreover, an outpost in Mohmand agency was hit June 11 in a U.S. strike that left 11 Frontier Corps soldiers — including a mid-level officer — dead.

On the U.S. side, rules of engagement stipulate very clearly the right to self defense — generally including preemptive self defense when the individual has a subjective sense of imminent hostile intent. Though more professional and restrained in a tactical sense, U.S. forces are likely to act aggressively to defend themselves once fired upon. In fact, U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates on Sept 23 told the Senate Armed Forces Committee that the United Nations Charter allowed the United States to act in self-defense against international terrorists in Pakistan if the government was unable, or unwilling to deal with them. Perceptions and misconceptions in such situations — on both sides — often make the situation all too quick to escalate.

Even though this particular incident may boil down to the innocent firing of signal flares, the situation has all the ingredients for significant escalation while politically and militarily — in a strategic sense — both sides remain in limbo. Pakistan does not have the military capability to establish its writ in FATA on its own without reducing its forces opposite India to what it considers unacceptable levels. The United States is not only in mid-stride during the final weeks of election season, but is facing domestic economic troubles and is still formulating its new strategy for Afghanistan.

In short, should things continue on this path, the situation may well get worse before there is any hope of it getting better.

Posted by

Richard Bowers

on

Sunday, September 28, 2008

0

Salutations and Rants

![]()

Labels: Canadian Forces, Jihad, Kings of the East, Other Military, Stratfor, U.S. and A

I can think of no more frightening phrase uttered in a time of crisis. With thanks to Bush's adventurism we now have a situation where the American military is spread a mile wide and an inch thick. The worst part is everybody - that being the Russians, the Iranians, the Israelis, the Saudis, and al-Qaida - know it. Whoever wins the White House is sure to have their resolve tested in 2009 at a time and place of our enemies choosing.

Johnny Cash

The Medvedev Doctrine and American Strategy

September 2, 2008

By George Friedman

The United States has been fighting a war in the Islamic world since 2001. Its main theaters of operation are in Afghanistan and Iraq, but its politico-military focus spreads throughout the Islamic world, from Mindanao to Morocco. The situation on Aug. 7, 2008, was as follows:

The war in Iraq was moving toward an acceptable but not optimal solution. The government in Baghdad was not pro-American, but neither was it an Iranian puppet, and that was the best that could be hoped for. The United States anticipated pulling out troops, but not in a disorderly fashion.

The war in Afghanistan was deteriorating for the United States and NATO forces. The Taliban was increasingly effective, and large areas of the country were falling to its control. Force in Afghanistan was insufficient, and any troops withdrawn from Iraq would have to be deployed to Afghanistan to stabilize the situation. Political conditions in neighboring Pakistan were deteriorating, and that deterioration inevitably affected Afghanistan.

The United States had been locked in a confrontation with Iran over its nuclear program, demanding that Tehran halt enrichment of uranium or face U.S. action. The United States had assembled a group of six countries (the permanent members of the U.N. Security Council plus Germany) that agreed with the U.S. goal, was engaged in negotiations with Iran, and had agreed at some point to impose sanctions on Iran if Tehran failed to comply. The United States was also leaking stories about impending air attacks on Iran by Israel or the United States if Tehran didn’t abandon its enrichment program. The United States had the implicit agreement of the group of six not to sell arms to Tehran, creating a real sense of isolation in Iran.

In short, the United States remained heavily committed to a region stretching from Iraq to Pakistan, with main force committed to Iraq and Afghanistan, and the possibility of commitments to Pakistan (and above all to Iran) on the table. U.S. ground forces were stretched to the limit, and U.S. airpower, naval and land-based forces had to stand by for the possibility of an air campaign in Iran — regardless of whether the U.S. planned an attack, since the credibility of a bluff depended on the availability of force.

The situation in this region actually was improving, but the United States had to remain committed there. It was therefore no accident that the Russians invaded Georgia on Aug. 8 following a Georgian attack on South Ossetia. Forgetting the details of who did what to whom, the United States had created a massive window of opportunity for the Russians: For the foreseeable future, the United States had no significant forces to spare to deploy elsewhere in the world, nor the ability to sustain them in extended combat. Moreover, the United States was relying on Russian cooperation both against Iran and potentially in Afghanistan, where Moscow’s influence with some factions remains substantial. The United States needed the Russians and couldn’t block the Russians. Therefore, the Russians inevitably chose this moment to strike.

On Sunday, Russian Prime Minister Dmitri Medvedev in effect ran up the Jolly Roger. Whatever the United States thought it was dealing with in Russia, Medvedev made the Russian position very clear. He stated Russian foreign policy in five succinct points, which we can think of as the Medvedev Doctrine (and which we see fit to quote here):

First, Russia recognizes the primacy of the fundamental principles of international law, which define the relations between civilized peoples. We will build our relations with other countries within the framework of these principles and this concept of international law.

Second, the world should be multipolar. A single-pole world is unacceptable. Domination is something we cannot allow. We cannot accept a world order in which one country makes all the decisions, even as serious and influential a country as the United States of America. Such a world is unstable and threatened by conflict.

Third, Russia does not want confrontation with any other country. Russia has no intention of isolating itself. We will develop friendly relations with Europe, the United States, and other countries, as much as is possible.

Fourth, protecting the lives and dignity of our citizens, wherever they may be, is an unquestionable priority for our country. Our foreign policy decisions will be based on this need. We will also protect the interests of our business community abroad. It should be clear to all that we will respond to any aggressive acts committed against us.

Finally, fifth, as is the case of other countries, there are regions in which Russia has privileged interests. These regions are home to countries with which we share special historical relations and are bound together as friends and good neighbors. We will pay particular attention to our work in these regions and build friendly ties with these countries, our close neighbors.

Medvedev concluded, “These are the principles I will follow in carrying out our foreign policy. As for the future, it depends not only on us but also on our friends and partners in the international community. They have a choice.”

The second point in this doctrine states that Russia does not accept the primacy of the United States in the international system. According to the third point, while Russia wants good relations with the United States and Europe, this depends on their behavior toward Russia and not just on Russia’s behavior. The fourth point states that Russia will protect the interests of Russians wherever they are — even if they live in the Baltic states or in Georgia, for example. This provides a doctrinal basis for intervention in such countries if Russia finds it necessary.

The fifth point is the critical one: “As is the case of other countries, there are regions in which Russia has privileged interests.” In other words, the Russians have special interests in the former Soviet Union and in friendly relations with these states. Intrusions by others into these regions that undermine pro-Russian regimes will be regarded as a threat to Russia’s “special interests.”

Thus, the Georgian conflict was not an isolated event — rather, Medvedev is saying that Russia is engaged in a general redefinition of the regional and global system. Locally, it would not be correct to say that Russia is trying to resurrect the Soviet Union or the Russian empire. It would be correct to say that Russia is creating a new structure of relations in the geography of its predecessors, with a new institutional structure with Moscow at its center. Globally, the Russians want to use this new regional power — and substantial Russian nuclear assets — to be part of a global system in which the United States loses its primacy. These are ambitious goals, to say the least. But the Russians believe that the United States is off balance in the Islamic world and that there is an opportunity here, if they move quickly, to create a new reality before the United States is ready to respond. Europe has neither the military weight nor the will to actively resist Russia. Moreover, the Europeans are heavily dependent on Russian natural gas supplies over the coming years, and Russia can survive without selling it to them far better than the Europeans can survive without buying it. The Europeans are not a substantial factor in the equation, nor are they likely to become substantial.

This leaves the United States in an extremely difficult strategic position. The United States opposed the Soviet Union after 1945 not only for ideological reasons but also for geopolitical ones. If the Soviet Union had broken out of its encirclement and dominated all of Europe, the total economic power at its disposal, coupled with its population, would have allowed the Soviets to construct a navy that could challenge U.S. maritime hegemony and put the continental United States in jeopardy. It was U.S. policy during World Wars I and II and the Cold War to act militarily to prevent any power from dominating the Eurasian landmass. For the United States, this was the most important task throughout the 20th century.

The U.S.-jihadist war was waged in a strategic framework that assumed that the question of hegemony over Eurasia was closed. Germany’s defeat in World War II and the Soviet Union’s defeat in the Cold War meant that there was no claimant to Eurasia, and the United States was free to focus on what appeared to be the current priority — the defeat of radical Islamism. It appeared that the main threat to this strategy was the patience of the American public, not an attempt to resurrect a major Eurasian power.

The United States now faces a massive strategic dilemma, and it has limited military options against the Russians. It could choose a naval option, in which it would block the four Russian maritime outlets, the Sea of Japan and the Black, Baltic and Barents seas. The United States has ample military force with which to do this and could potentially do so without allied cooperation, which it would lack. It is extremely unlikely that the NATO council would unanimously support a blockade of Russia, which would be an act of war.

But while a blockade like this would certainly hurt the Russians, Russia is ultimately a land power. It is also capable of shipping and importing through third parties, meaning it could potentially acquire and ship key goods through European or Turkish ports (or Iranian ports, for that matter). The blockade option is thus more attractive on first glance than on deeper analysis.

More important, any overt U.S. action against Russia would result in counteractions. During the Cold War, the Soviets attacked American global interest not by sending Soviet troops, but by supporting regimes and factions with weapons and economic aid. Vietnam was the classic example: The Russians tied down 500,000 U.S. troops without placing major Russian forces at risk. Throughout the world, the Soviets implemented programs of subversion and aid to friendly regimes, forcing the United States either to accept pro-Soviet regimes, as with Cuba, or fight them at disproportionate cost.

In the present situation, the Russian response would strike at the heart of American strategy in the Islamic world. In the long run, the Russians have little interest in strengthening the Islamic world — but for the moment, they have substantial interest in maintaining American imbalance and sapping U.S. forces. The Russians have a long history of supporting Middle Eastern regimes with weapons shipments, and it is no accident that the first world leader they met with after invading Georgia was Syrian President Bashar al Assad. This was a clear signal that if the U.S. responded aggressively to Russia’s actions in Georgia, Moscow would ship a range of weapons to Syria — and far worse, to Iran. Indeed, Russia could conceivably send weapons to factions in Iraq that do not support the current regime, as well as to groups like Hezbollah. Moscow also could encourage the Iranians to withdraw their support for the Iraqi government and plunge Iraq back into conflict. Finally, Russia could ship weapons to the Taliban and work to further destabilize Pakistan.

At the moment, the United States faces the strategic problem that the Russians have options while the United States does not. Not only does the U.S. commitment of ground forces in the Islamic world leave the United States without strategic reserve, but the political arrangements under which these troops operate make them highly vulnerable to Russian manipulation — with few satisfactory U.S. counters.

The U.S. government is trying to think through how it can maintain its commitment in the Islamic world and resist the Russian reassertion of hegemony in the former Soviet Union. If the United States could very rapidly win its wars in the region, this would be possible. But the Russians are in a position to prolong these wars, and even without such agitation, the American ability to close off the conflicts is severely limited. The United States could massively increase the size of its army and make deployments into the Baltics, Ukraine and Central Asia to thwart Russian plans, but it would take years to build up these forces and the active cooperation of Europe to deploy them. Logistically, European support would be essential — but the Europeans in general, and the Germans in particular, have no appetite for this war. Expanding the U.S. Army is necessary, but it does not affect the current strategic reality.

This logistical issue might be manageable, but the real heart of this problem is not merely the deployment of U.S. forces in the Islamic world — it is the Russians’ ability to use weapons sales and covert means to deteriorate conditions dramatically. With active Russian hostility added to the current reality, the strategic situation in the Islamic world could rapidly spin out of control.

The United States is therefore trapped by its commitment to the Islamic world. It does not have sufficient forces to block Russian hegemony in the former Soviet Union, and if it tries to block the Russians with naval or air forces, it faces a dangerous riposte from the Russians in the Islamic world. If it does nothing, it creates a strategic threat that potentially towers over the threat in the Islamic world.

The United States now has to make a fundamental strategic decision. If it remains committed to its current strategy, it cannot respond to the Russians. If it does not respond to the Russians for five or 10 years, the world will look very much like it did from 1945 to 1992. There will be another Cold War at the very least, with a peer power much poorer than the United States but prepared to devote huge amounts of money to national defense.

Four Broad U.S. Options

Attempt to make a settlement with Iran that would guarantee the neutral stability of Iraq and permit the rapid withdrawal of U.S. forces there. Iran is the key here. The Iranians might also mistrust a re-emergent Russia, and while Tehran might be tempted to work with the Russians against the Americans, Iran might consider an arrangement with the United States — particularly if the United States refocuses its attentions elsewhere. On the upside, this would free the U.S. from Iraq. On the downside, the Iranians might not want —or honor — such a deal.

Enter into negotiations with the Russians, granting them the sphere of influence they want in the former Soviet Union in return for guarantees not to project Russian power into Europe proper. The Russians will be busy consolidating their position for years, giving the U.S. time to re-energize NATO. On the upside, this would free the United States to continue its war in the Islamic world. On the downside, it would create a framework for the re-emergence of a powerful Russian empire that would be as difficult to contain as the Soviet Union.

Refuse to engage the Russians and leave the problem to the Europeans. On the upside, this would allow the United States to continue war in the Islamic world and force the Europeans to act. On the downside, the Europeans are too divided, dependent on Russia and dispirited to resist the Russians. This strategy could speed up Russia’s re-emergence.

Rapidly disengage from Iraq, leaving a residual force there and in Afghanistan. The upside is that this creates a reserve force to reinforce the Baltics and Ukraine that might restrain Russia in the former Soviet Union. The downside is that it would create chaos in the Islamic world, threatening regimes that have sided with the United States and potentially reviving effective intercontinental terrorism. The trade-off is between a hegemonic threat from Eurasia and instability and a terror threat from the Islamic world.

We are pointing to very stark strategic choices. Continuing the war in the Islamic world has a much higher cost now than it did when it began, and Russia potentially poses a far greater threat to the United States than the Islamic world does. What might have been a rational policy in 2001 or 2003 has now turned into a very dangerous enterprise, because a hostile major power now has the option of making the U.S. position in the Middle East enormously more difficult.

If a U.S. settlement with Iran is impossible, and a diplomatic solution with the Russians that would keep them from taking a hegemonic position in the former Soviet Union cannot be reached, then the United States must consider rapidly abandoning its wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and redeploying its forces to block Russian expansion. The threat posed by the Soviet Union during the Cold War was far graver than the threat posed now by the fragmented Islamic world. In the end, the nations there will cancel each other out, and militant organizations will be something the United States simply has to deal with. This is not an ideal solution by any means, but the clock appears to have run out on the American war in the Islamic world.

We do not expect the United States to take this option. It is difficult to abandon a conflict that has gone on this long when it is not yet crystal clear that the Russians will actually be a threat later. (It is far easier for an analyst to make such suggestions than it is for a president to act on them.) Instead, the United States will attempt to bridge the Russian situation with gestures and half measures.

Nevertheless, American national strategy is in crisis. The United States has insufficient power to cope with two threats and must choose between the two. Continuing the current strategy means choosing to deal with the Islamic threat rather than the Russian one, and that is reasonable only if the Islamic threat represents a greater danger to American interests than the Russian threat does. It is difficult to see how the chaos of the Islamic world will cohere to form a global threat. But it is not difficult to imagine a Russia guided by the Medvedev Doctrine rapidly becoming a global threat and a direct danger to American interests.

We expect no immediate change in American strategic deployments — and we expect this to be regretted later. However, given U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney’s trip to the Caucasus region, now would be the time to see some movement in U.S. foreign policy. If Cheney isn’t going to be talking to the Russians, he needs to be talking to the Iranians. Otherwise, he will be writing checks in the region that the U.S. is in no position to cash.

This report may be forwarded or republished on your website with attribution to Stratfor.com

Posted by

Richard Bowers

on

Wednesday, September 03, 2008

0

Salutations and Rants

![]()

Labels: Jihad, Other Military, Russia, Stratfor, U.S. and A

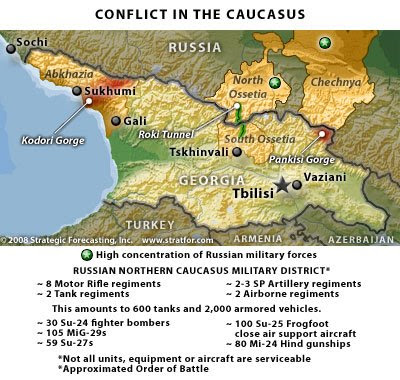

Hard to ignore what's going on in the southern periphery of Russia. Decided to post these nifty maps from Stratfor. The most recent are at the top. Is this a precursor to further Russian military action in its 'Near Abroad'? Is Ukraine next? The real issue here is what will the Russian strategy be after Georgia. No doubt those on Russia's borders are swallowing hard. Read Ezekiel 38-39 for reference. In the meantime, pray for peace and an end to hostilities in the region.

Johnny Cash

Posted by

Richard Bowers

on

Monday, August 11, 2008

0

Salutations and Rants

![]()

Labels: Other Military, Russia, Stratfor

In the twentieth century, two massive events occurred in May. In 1945, the fall of Nazi Germany ended one of the most destructive wars in all of human history. Three years later on May, 14, 1948, the re-birth of the state of Israel shook the world and foreign governments.

Before we look at Israel's modern day rebirth, we must first look at the three captivities that Israel endured. The first two were regional in nature, the third captivity was worldwide.

The First Captivity: Egypt

Now the length of time the Israelite people lived in Egypt was 430 years. At the end of the 430 years, to the very day, all the LORD's divisions left Egypt. (Exodus 12:40-41)

Here's the best part:

The Israelites did as Moses instructed and asked the Egyptians for articles of silver and gold and for clothing. The LORD had made the Egyptians favorably disposed toward the people, and they gave them what they asked for; so they plundered the Egyptians. (Exodus 12:35-36)

To the very day the Israelites were driven out by the Egyptians. There was no escape here, they were pushed out! Moreover, they actually plundered the Egyptians prior to leaving and were laden with gold, silver and clothing. I don't know about you, but this absolutely blows my mind. The exodus happened to the very day that God promised to Abraham and were made rich with parting gifts in the process.

The Second Captivity: Babylon

This whole country will become a desolate wasteland, and these nations will serve the king of Babylon seventy years. "But when the seventy years are fulfilled, I will punish the king of Babylon and his nation, the land of the Babylonians, for their guilt," declares the LORD, "and will make it desolate forever." (Jeremiah 25:11-12)

Notice the seventy year cycle. As I mentioned in 'Pentecost 2017', seventy years was often used to purify and sanctify God's people from sin. After King Cyrus of Persia allowed the Jewish people to leave and go back to Jerusalem, a partial return in unbelief was the result.

The Third Captivity: Worldwide

The prophet Ezekiel was given an odd task setting the stage for the rebirth of modern Israel in May of 1948:

"Then lie on your left side and put the sin of the house of Israel upon yourself. You are to bear their sin for the number of days you lie on your side. I have assigned you the same number of days as the years of their sin. So for 390 days you will bear the sin of the house of Israel. "After you have finished this, lie down again, this time on your right side, and bear the sin of the house of Judah. I have assigned you 40 days, a day for each year. (Ezekiel 4:4-6)

So 390 days plus 40 days equals 430 years, seeing as one day symbolizes a year. Of those 430 years, 70 years was subtracted due to Israel's captivity in Babylon. That leaves us with 360 years of judgement. However, these years were multiplied by seven due to their unbelief:

If after all this you will not listen to me, I will punish you for your sins seven times over. (Leviticus 26:18)

If you remain hostile toward me and refuse to listen to me, I will multiply your afflictions seven times over, as your sins deserve. (Leviticus 26:21)

Those 360 years is now multiplied by a factor of seven. 360 x 7 = 2520 Biblical years (comprised of 360 days each). Divide 907, 200 days (2520 x 360 = 907,200) by 365.25 (the solar year to which we are accustomed) and you get 2,483.778 calendar years. So from 606 B.C. to the spring of 536 B.C. was seventy years of captivity under Babylonian rule. God's people then partially return in unbelief according to Cyrus' decree.

According to our logic, we add 2,483.8 calendar years to the year 536 B.C. (keeping in mind there was no year between 1 B.C. and 1 A.D.) we get:

May 14, 1948.

Israel's third captivity comes to a close and modern day Israel is reborn, exactly right on time.

Kudos to Grant Jeffrey

You didn't think I could come up with this all by myself did you? My research is based on Grant Jeffrey's book Armageddon: Appointment With Destiny. To be precise, Chapter 3: Ezekiel's Vision of the Rebirth of Israel in 1948 is where all this information is found.

So is Israel's Rebirth Really an al-Naqba/Disaster?

It is for those that oppose the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. As the star of Bethlehem heralded the First Advent, the Star of David on Israel's flag heralds the Second Advent. No wonder the unbelievers are terrified! Even so, come Lord Jesus!

Johnny Cash

Posted by

Richard Bowers

on

Sunday, May 18, 2008

0

Salutations and Rants

![]()

Labels: Anti-Semitism, Bible Prophecy, Christian Theology, Holy Land, Persecution, Stratfor

Negotiate with the Taliban? Only if Jack Layton is leading the charge. That way if anything happens to him it won't be considered a huge loss. Just kidding Jack! I once met Mr. Layton and shook his hand. He sure knows how to charm the Danforth locals. On a more serious side this really reflects unfavorably upon NATO. I sure hope PM Stephen Harper is playing close attention to this.

Johnny Cash

Geopolitical Diary: Negotiating With the Taliban in Afghanistan

May 2, 2008 0201 GMT

Canadian troops in Afghanistan are looking for opportunities to carry out tactical-level talks with Taliban insurgents, Canadian newspaper Globe and Mail reported on Thursday. The paper added that discussions are under way in Afghan government circles regarding strategic negotiations with the Taliban, including some controversial suggestions that Taliban leaders could receive political appointments or provincial governing posts. Furthermore, international stakeholders in the Policy Action Group reportedly are discussing “red lines” to set boundaries for what the talks could include.

The West has come to the realization that “solving” Afghanistan is not something that can be done militarily. The country, with its size and geographic complexity, is — at best — an artificial state held together by nothing more than an occupying force and neighbors who think that imposing direct control is more trouble than it is worth. Put another way, if the Soviets — with as many troops in Afghanistan as the United States now has in Iraq and with the will to kill anyone, anywhere — could not handle the country, NATO will certainly not be able to handle it with Western rules of engagement.

Yet that is how the war has been fought since 2002. Note we say 2002, not 2001. In 2001, the war was a different creature: The operation entailed overthrowing the then-Taliban government, and not imposing some flavor of stability. Overthrowing a manpower-light, geographically dispersed military proved rather simple. But then again, most of the Taliban chose not to stand still and let themselves be bombed from 20,000 feet; they melted away into the countryside. They began their resurgence in 2002 — which, six years later, has taken the form of a full-fledged insurgency.

The state of war that has existed since the Taliban began their comeback is what has defined the “country” for the past six years. And that war is what the U.S. administration is now attempting to redefine. The first step in that process is the installment of Gen. David Petraeus as chief of U.S. Central Command.

Petraeus’ most impressive claim to fame so far was turning the Iraqi war of occupation around. Instead of using military force to make Iraq look like a sandy Wisconsin, he instead engaged select foes and turned them into allies, adding American firepower to their own. This not only whittled down the number of militants fighting U.S. forces, but it allowed those forces to concentrate their efforts on the foes that they had to fight, instead of needing to patrol regions that — with the right deals cut — could patrol themselves.

The war in Iraq is hardly “over,” but Petraeus’ strategy has proven sufficient to make the task manageable. Perhaps there are lessons from Iraq that can be put to work in Afghanistan such that the United States and its NATO allies can reach a point where the chaos there can be managed as well. If re-Baathification worked and the Americans are working with Islamist actors in Iraq (both Sunni and Shiite), perhaps they can do the same in Afghanistan. In other words, if there is a need to bring back the Taliban, then that has to be managed.